Growing up in Romania meant being exposed to my country’s tarnished reputation thanks to the sustained work of isolationist media outlets. There wasn’t a day you wouldn’t hear the label “thief” or “beggar” tossed around in relation to my nationality. Eastern European states already display a strong inferiority complex; add negative stereotypes to that and you will create people that are so insecure and defensive that they only exist to disprove what’s been said about them. The Romanian and the Polish are wanderers of the world. Over the years, they’ve systematically fled poverty, horrible political climates and intellectual stagnation in places that could not sustain development. It’s normal to run from these things. I’m sure this is true for many other nations as well.

I took all of these contradictory feelings and fears with me every time I left my country when I first began travelling. I was always surprised that people didn’t hate me because of where I happened to have been born. My hope in human interconnectedness was renewed with every new person that became my friend. In the autumn of 2018, I took part in a training session in Portugal which made me realize how much being abroad had changed me. My colleagues were asked to write stereotypes about my nationality on sticky notes and put them on my body. Amusingly enough, we all found this exercise extremely difficult and ended up writing generic insults on the notes to get it over with. This group was made up of people who tried to rise above gratuitous negativity. These were my friends, who never looked at me through the lens of my nationality. Despite our best efforts to treat this whole thing as a joke, the past caught up with me: I found myself quite literally labeled “poor”, “stupid” and “beggar”, the same words I would hear on TV when I was young. The major difference was that now I had grown up and widened my horizons. I knew none of those characteristics had anything to do with me.

I wasn’t the only one that the labels had turned thoughtful: everyone wore their own and shuffled around the room with intrigued looks in their eyes. The light-hearted atmosphere had changed. We resisted being branded thus. Many asked “When will we take these off?” The discussion that followed the exercise was contrastively uplifting though: we concluded that it was dangerously easy to throw around these unmerited words. Even if these labels weren’t representative, it had taken mere minutes for us to internalize them. It’s so difficult to dissolve a stereotype: it takes a joint effort from the observer and the observed. The problem is, these two sides can’t always meet. Not everyone has the means to experience the transformative powers of travel. This is exactly why Erasmus is of vital importance. When I went on mobility to Italy, my family was overjoyed. My father had worked there during his youth as an illegal immigrant; the Communist regime had a habit of denying people the right to move freely outside borders, so he had run off in a desperate attempt at freedom. The story had come full circle: his daughter would be returning to that same country to study among peers.

Even when living in Perugia, I enjoyed navigating others’ innocent confusion regarding my nationality. It was never as harsh as the (in)famous notes from the Portuguese training session. A pair of German friends asked me if my language uses the Cyrillic alphabet. I’d been telling them time and time again that I basically speak a Slavic Italian, so I guess that curiosity was somehow justified. After talking to my mother or my friends, I heard remarks along the lines of “Your language is strange.” and “Your language sounds like Russian.” It seemed to me that for a lot of Westerners, the Eastern states were still some Russian excrescence with no national identities of their own. Even being Russian was reduced to two or three undying stereotypes: beautiful women, vodka and track suits. That being said, it seems more important than ever to remind people that every culture brings value through variety to the world we live in and to be reductionist is to lose the opportunity to live fully. It’s ridiculous to think that a country is merely one or two things, just as a human being has a multitude of facets.

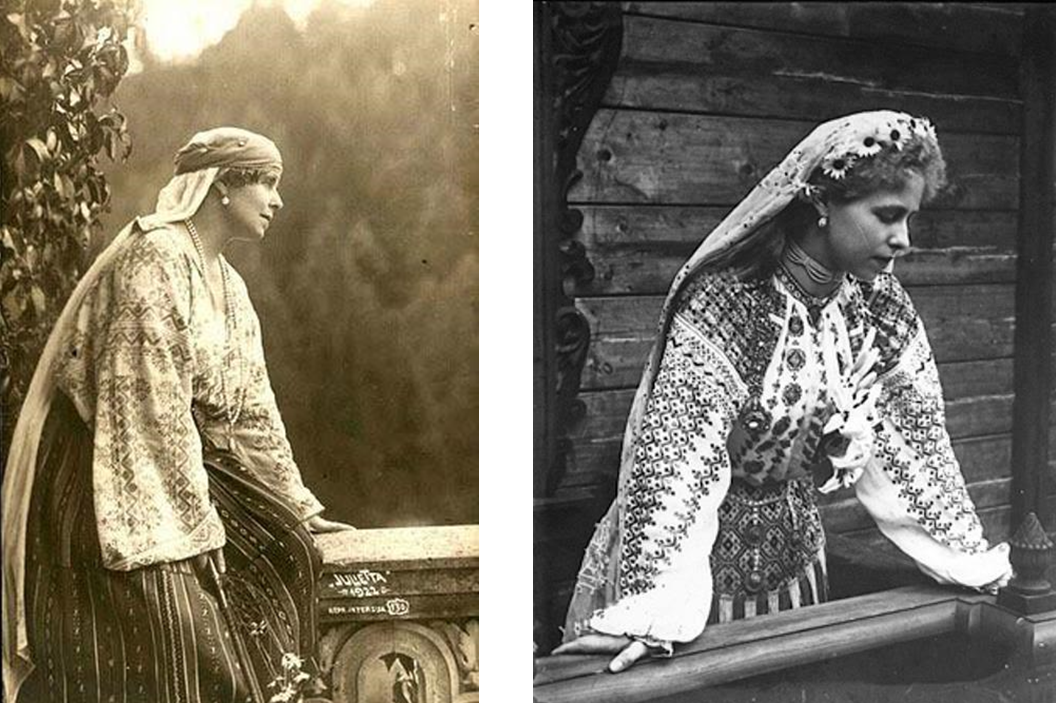

One day, I got homesick and wore a traditional blouse (called “ie”). A Belgian friend remarked “What’s Romanian about this? So many girls wear peasant blouses. It’s been fashionable since the ‘80s.” She was right, but that fashion had roots in the design of the “ie”. I once remarked that dolma (szarma, sarmale) were a Balkan food we cooked variations of on holidays; the same friend defended it as an exclusively Greek dish. It was amusing and perplexing for me to see how little people knew about my culture, but I appreciated the passionate debates and interest nonetheless. I flooded them with pictures of the mountain landscapes and villages. I taught Romanian words to whoever wanted to learn them. I left someone a recipe for my mother’s polenta (we call it mămăligă, it’s quite the mouthful). I was moved by everyone’s determination to visit and see for themselves. Only this questioning and curious spirit can melt away preconceived ideas.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, those very knowledgeable and sympathetic shook me to my core. I was completely taken aback when the Brazilian translator of “Ulysses”, Caetano Galindo, approached me speaking perfect Romanian at the Trieste Joyce School. A Japanese exchange student named Yoshiro Sakamoto stunned my entire faculty a couple of years back with his extensive knowledge of both the language and a long-forgotten Romanian poet that had become an exile in Hawaii during the communist regime. A Napoletan gentleman I sat next to while coming home from Hungary told me all about how his son married a Romanian woman and moved to Maramures. The staff of Universidade do Minho had complete confidence that I could learn a wonderful continental Portuguese simply because I was Romanian.

Romania is a tough place to start out in, but it has its charm nonetheless. Becoming part of the EU made my generation feel seen, valued and anchored in normalcy. No matter your feelings towards my little fish-shaped country, keep in mind that it’s more than the birthplace of vampire stories. Do not hate the poor for being poor, do not hate the weak for being weak. Exercise empathy, share the strength you so fortunately possess. Special thanks to the many generations of Erasmus students that have come to Cluj-Napoca and have done just that. To the rest of you, come visit us. Eat our food, listen to our music and our strange words. I’m sure we can be great friends.